Ever wondered how that spoon full of tea arrived in your teapot? You might shovel the tea leaves into the teapot without a second thought for the multitude of processes that went into getting the tea to that perfect moment of taste. I decided to find out.

So how is tea made? It’s a linear process beginning with growing and harvesting leaves of the Camellia Sinensis plant. The extent of further processing depends on the type of tea required. Processing includes harvesting, withering, rolling, oxidizing, drying, and grading. Let’s take you through the process.

How Tea is Made – Camellia Sinensis

Camellia Sinensis is an evergreen plant and a member of the Theaceae family of shrubs. In the wild

Leaves grow up to around 3.5” or 9cm long by 1.5” or 3cm wide in a spearhead shape with a center crease and softening blackening towards to tips. They’re bright green and have a shiny texture, with soft downy hair underneath.

The plant has a number of points during its growing season at which it flowers, known as a ‘flush’, the flowers are slightly scented and hold a collection of yellow stamens which are pollinated by insects.

Ideal Growing Conditions

Tea isn’t just grown in controlled conditions it grows in the wild too. nonetheless, tea ideally grows best in more equatorial regions, which enjoy a hot, or warm, humid climate with an approximate rainfall measuring 40 inches /100 centimeters a year.

Camellia Sinensis roots better in deep, acidic, and airy soil where good drainage exists. In ideal conditions, you can expect to grow the plant right from sea level to over 2,000 meters.

It’s hardy when mature but in the early stages, it needs nursing well and kept in heavy shade or protection from frost – up until about 1’ or, 30 cm tall.

Although Ideal, it doesn’t only have to be grown in tropical or sub-tropical climates.

Where Is Tea Grown?

The tea plant is a tropical plant indigenous to India and China and resembles what most might regard as a privet hedge.

Originally, Tea plants were grown in China, Japan, India, Sri Lanka (formerly Ceylon), and Taiwan. However, Tea is now manufactured in dozens of countries is possible providing suitable conditions are met.

In Northern India, the states of West Bengal and Assam in particular are littered with plantations that form a large part of the economy.

Now tea has become more popular, it’s being grown in both the USA and Britain to for example to great success.

Here’s where tea is grown, showing the amounts in each country.

1. Seeding Process

Tea Plants begin life as large soft round seedlings, about 1/2” – 3/4” in diameter. The seedling is placed in water for around 24-48 hours to kickstart the germination process.

The seeds are then left in full sunlight, again for around 24-48 hours, sometimes longer depending on weather or controlled conditions.

Once the shell begins to split, the seed is then planted around an inch below deep airy soil, with the ‘Hilum’ or the eye of the seed facing upward. They are then left, taking care not to leave them in harsh weather conditions as they’re not yet hardy enough to withstand it.

Once they reach around a foot tall, they’re then planted outside. Usually in a field where wide shaded trees are also present to provide shelter from continuous direct sunlight.

As the plant requires plenty of water and a well-drained environment, in controlled environments the fields are often lined with irrigation systems.

2. Growing The Tea Plant

Once the tree has reached a height of around 4 feet, it’s kept at this optimum level from this point on, solely for ease of harvesting.

It can take around 4 years before a tree is hardy enough to begin cultivation, so this is a waiting and nurturing game.

Each time the plant creates new shoots and leaves they’re harvested. This could be just 2-3 times a year. However, this can occur more often in places such as Sri Lanka, Indonesia, Kenya, or in the south of China and India where summer is all year round. Harvesting becomes less infrequent the further north you travel.

For example, North India has an 8-month harvesting season. In Northern China, harvesting can be around 4 times a year from around April to September.

During the harvesting season means tea can be harvested from each field every 5 to 8 days

3. Harvesting / Picking

Tea is a manual harvesting process, people harvest by hand or using specialist pruning shears with a collection basket attached. They have a basket on their back to which the harvested leaves are added to.

The reason for a manual process is quality control. The experienced pickers know which buds are ripe for the picking and are able to pick the best ones.

Pickers only collect leaves from the top of the tea plant – known as the ‘Flush’, these have one or two leaves, an unopened bud, and part of the new step. Where a flush has 2 or 3 leaves, this is known as a golden flush.

In order to be this precise in the selection, hand-picking is far superior, so where possible, avoid teas that have been machine picked.

In the case of Oolong tea, hand picking is essential to avoid any bruising occurring to the leave before processing.

The leaves are weighed, added to bags, and sent to the factory. As speed is now important to prevent deterioration of the stock, trucks are sent from the fields to the factories often up to 4 times a day.

4. Withering

Once at the factory, leaves are quickly weighed and inventoried, then spread out over large white cloths laid on the ground – like decorators’ sheets. is where manufacturing begins to separate out the different types of tea, Black, White, Oolong, Green (and Pu-erh).

Generally speaking, leaves are left to ‘solar dry’ in the sun to wither, which can remove up to 50% or even 60% of their moisture content. They are shuffled regularly to provide an even process and often conditioned air is circulated around them to speed up the process by drying up any surface water content and aiding the chemical breakdown of the juices.

This process alone can take 12 to 18 hours to complete – again depending on how thin you spread the leaves, and the type of tea required. Black tea, for example, is oxidized for longer and therefore the leaves are spread into thinner layers.

The main objective of withering is to soften the leaves, this removes any brittle tendencies from the stems which means they’ll withstand the rolling process.

Once the plant is softened enough that the stem can be bent in half – then it’s ready for further oxidizing and then rolling. At this stage, the essential enzymes and polyphenols are still present in the leaves.

5. Oxidation / Fermentation

Black tea – which is the most processed. The tea is piled up in a container or on tiled or glass tables. It is then covered from direct sunlight and left to

As this continues, the leaves will turn from an oily green to a copper-like color and this is how the degree of fermentation is gauged. Also, the pile will become quite warm as it’s heated by the sun, and from within as the enzymes work under the surface to enhance the flavor.

The alternative and more industrial method are to dry the tea with hot air, by roasting, or in the case of Japanese tea – steaming. the temperature at which the tea is heated will enable the oxidization process to be fixed so that no further oxidation occurs.

6. Rolling

Leaves are then wrapped up into cloth bundles and rolled manually at first, then in a specialist rolling machine. This releases further moisture prior to the oxidation and fermentation process.

The act of rolling breaks and ruptures the cell walls, bringing the essential juices to the surface of each leaf.

Rolling machines can come in various forms, depending on the amount of manufacturing that takes place. A typical machine will have a cylinder in which to place the tea, and a pressure plate that inserts into the top of the cylinder, applying downward pressure.

The whole cylinder containing the tea is then mechanically driven in a circular movement over a metal base with a meters cone. This is designed to roll and curl the leaves. Think of it almost as a giant food mixer effect with a cone spiral up the

The rolling process takes around 30 to 60 minutes to complete.

7. Drying / Fixing

Drying, or firing, is required in order to help ‘Fix’ the oxidation process, i.e. prevent further oxidation. Also, it’s designed to extract any remaining moisture from the leaves.

The driers consist of perforated trays that are passed on a conveyer beneath hot machine driers for around 20 to 30 minutes. To begin with, the teas have a 50% moisture content.

The starting temperature when tea is introduced is 120 degrees or 50 degrees Celcius, this increases to 200 degrees, which is about 93 degrees Celsius.

When completed the moisture content should have reduced from 50% down to 3%. The color of the tea will have changed by this time, from a copper brown mix to a black mix.

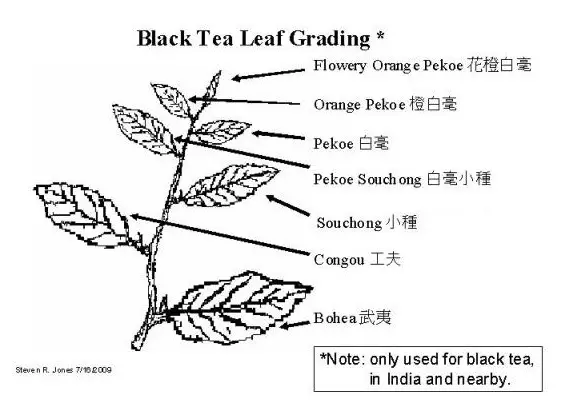

8. Grading

The resulting tea is passed through grading machines to filter them into their respective grades using a series of grading and sifting machinery. Differing mesh sizes ‘sort’ the tea leaves into their respective sizes. This is all based on size. Below I’ve added a grading table for easy reference.

9. Testing

Once the tea has been fully processed, it undergoes sporadic and systematic taste testing by the tea masters to ensure the quality of the product is maintained, before being sealed in air-tight containers…

10. Packing / Despatching

Because of the dryness of the finished product. Teas can easily absorb moisture.

The packing process usually involves tightly packing the tea in plywood tea chests, which also contain several layers of aluminum craft paper sacks.

From there the tea is either transported to auction houses or packed in specific packaging for direct export shipment.

11. Shipping & Transportation – (The Tea Commodity Chain)

Sri Lanka

Upon leaving the plantations, Tea leaves are either sent directly to a processing center or through bought leaf suppliers.

Akbar brothers and Hayleys are Sri Lanka’s largest exporters of tea. Sri-Lankan Tea manufacturers and Tea suppliers control a majority share of the global tea market.

China

China has strict contamination checks on any tea exports. All tea is put into airtight containers and is checked for contaminants before being shipped.

These shipments are destined for predominant foreign markets like Russia, Morocco, Japan, and the United Kingdom. Morocco is known to be the highest importer of Chinese Tea.

However, Tea is exported with minimal processing to their respective importing countries, where in turn the arriving tea is further blended by tea companies. Often in processing for ‘Ready to use’ tea for consumer use.

India

A shorter journey is required. Mostly Tea is shipped by truck and/or railroad within the borders of India. It is rarely shipped further from here. India primarily uses their homegrown tea for their own consumption.

When tea IS exported, the majority are sent via shipping containers. The containers must however be watertight and be placed below deck in order that the tea is unaffected by weather such as rain, or even any effects from seawater. Even the temperature has to be monitored so as not to get too hot or too cold.

The primary tea shipping ports in India are Jawaharlal Nehru Port, Kochi, New Mangalore, Kolkata-Haldia, and Chennai.

Darjeeling tea from Northern India is sent via air freight for the most part. this speeds up the delivery process – rather than pass through all of India first.

Tea from India is mostly exported to the United Kingdom, Russia, UAE, and Iran.

To Your local Store

Once arriving, the teas are shipped to the importing country. It is then sent through distribution channels to arrive at your local store.

Now, Let’s look at how each type of tea differs in the above production process.

Production: Specific To Each Tea Class

Now, Let’s look at how tea production differs for each of the varieties of teas.

For the most part, tea has always been classified based on the degree of oxidation (or fermentation its been subjected to. You will see from the categories below that it’s predominantly the process of withering and oxidation that can create such varieties.

In this next section, we also introduce an additional tea class not mentioned previously, mainly as it’s not as common, but is still grown in small quantities.

It rests between Green and White tea and is called Yellow Tea. Made famous when the emperors of China commonly drank it – yellow being the imperial color. these days, Yellow Tea is commonly given as an overseas gift.

Green Tea

The least amount of oxidation time is taken to produce green Tea. Hence the name, the whole processing is done within one or two days of harvesting.

The oxidation process is ceased when a short blast of heat is applied shortly after being picked. This is done using Steam – which is the preferred method in Japanese Processing. Or Heat, or ‘dry roasting’, which is predominantly the Chinese method.

The leaves are then either dried as they are, or rolled into small pellet-shaped balls. As this process takes an amount of time, it’s usually done with the higher grade Pecoe Tea. If the process is followed correctly, it should produce a crop that contains the right amount of chemical composition.

When steamed, the color and brightness of the tea are more apparent. When dry roasting is used, the crop tends to be darker, but richer in taste.

There are further alterations in flavor that can occur when the tea is subjected to variations in rolling, steaming or fixation or simply by extending or shortening the times of all of the processes.

Yellow Tea

Processed much the same way as Green Tea, However, the chlorophyll part of the leaves is the main target during processing. Rather than immediately drying the leaves after the fixation phase, the leaves are spread out in trays and covered where they are then heated gently in a humid environment. Oxidation is commenced in the Chlorophyll without affective enzymes or microbial elements.

The result is a green to yellow color of tea that is smooth, with a natural fragrance and rich flavor.

White Tea

Made with only new shoots, leaves, and buds harvested from the plant. Again the oxidation process is limited with just a slight added amount of solar withering. They are then Dry roasted at 30 degrees, or steamed at 65 degrees for about 25 hours, this will cease the oxidation process.

The total withering time can be anything between 1 to 3 days depending on the temperatures at the time of year and the seasonal variances in the harvest. The lack of fixation means the white (or silver) hairs on the underside of the leaves are retained, which is where White Tea earns its name.

Rarer than other types of tea (except Yellow) and produces a very mild taste and yet despite its lack of processing white tea tends to be more expensive than other tea variations.

Oolong Tea

Produced in large quantities in Taiwan and the name was given to a particularly semi-oxidized tea. Oolong falls between Green and Black tea inherently due to its oxidation process being between the two. As with white tea, the withering process can take 2 to 3 days. But then adds a short oxidation process of up to 7 hours.

Likewise, Darjeeling tea undergoes a similar process and becomes more akin to Green or Oolong tea. Teas that are semi-oxidized are referred to in China as Blue teas, or blue-green teas.

It is commonly thought – particularly in Taiwan, that oxidization over too short a time period can be too raw and upsetting for the average consumer’s stomach. However, the process is still carried out in order to produce a specific taste or texture. Minimal oxidation also allows the leaves to be rolled into balls easier- which is desirable across some markets.

Black Tea

Full oxidization takes place with black tea, allowing it to wither completely to enable the breaking down of proteins, leading to a softening of the leaves and stems and a much-reduced water content down to around 50% to 75%.

Unlike other teas, black tea then undergoes a process called ‘Disruption’ where the leaves’ cell structures are subjected to bruising, cutting, and bending. This brings enzymes to the surface of the leaves that assist in activating oxidation.

Oxidation takes place for between 1 to 3 hours in the high humidity of around 30 degrees Celsius. Complex and rich tannins are produced from a transformation in catechizes within the leaves.

Black tea also undergoes a heavy rolling process to further break down the leaf structure, which then also provides a mix of whole and broken leaves and remaining particles.

The Orange Pekoe system is used to grade the teas before oxidization, although this can differ slightly where CTC (Crush, Tear, Curl) machinery is used.

To produce fine tea – fanning and dust that is used for teabags, a machine developed in 1930 by William McKercher were developed which crushes and cuts the leaves to an even size ready for tea bag use.

Post Fermented Tea

The final category is different again. Teas that undergo further second oxidation after the ‘Fixing’ process are post-fermented. Common teas of this type are Pu-erh, Liubao, and Liu’an. In China, these are referred to as ‘Dark Teas’ or ‘Black Teas’. In English, they’re referred to as secondary, or post-fermented teas.

You can see the full flow diagram of how this process works HERE

I hope this has helped you to understand the process of tea manufacturing from start to finish. Next time you’re pouring a cup of Oolong, or Green, perhaps you wouldn’t mind sparing a thought for the time, energy, and hours – in fact, years, that it took for those leaves, to arrive in your cup.